My first week in West Texas felt like living a Hunter S. Thompson dispatch narrated by Anthony Bourdain

There’s a kind of silence in West Texas that you don’t hear anywhere else. It’s not peaceful. It’s not meditative. It’s a silence that weighs on your shoulders like a dare. It stares back. Between El Paso and the Big Bend, the land doesn’t care if you’re watching. It isn’t trying to impress you. It just is. Harsh, honest, stripped down to its bones. The desert leaves only what matters. Marfa, Valentine, Van Horn, and Fort Davis dot the landscape like sparse punctuation marks in a sprawling epic.

Van Horn is just off I-10 a couple of hours east of El Paso; the exit to Highway 90 starts the 75-mile straight shot across bumpy and windy desert asphalt to Marfa. You better not run out of gas.

Border Patrol checkpoints punctuate the highways, silent reminders of the fraught realities that lie beneath the scenic beauty. Officers with wary eyes scan cars methodically, their presence a stark contrast to the surrounding emptiness. Drones and blimps fill the air. It’s strange—how freedom and surveillance walk hand and hand in this desert. I get pulled over outside of Van Horn. The agent was polite, asked if I had anyone hiding in the back seat. Just ghosts.

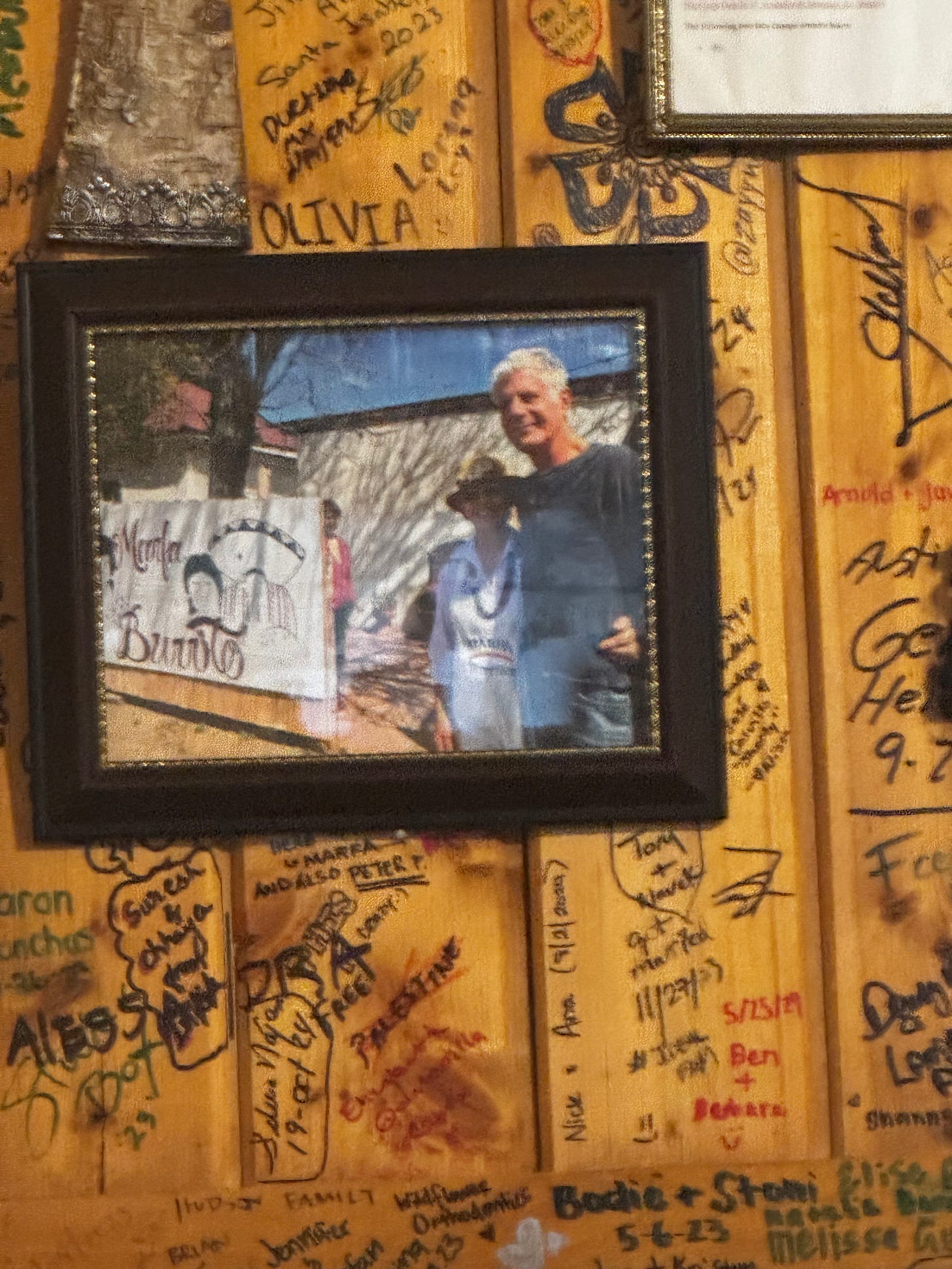

Rolling into Marfa, the sky stretches out, impossibly big, a dome painted with wisps of white and endless shades of blue. It’s a town that feels like a half-remembered dream: a paradoxical mix of artists, cowboys, hipsters, and ranchers living side by side. Everyone talks about Marfa like it’s some art-world Shangri-La. And yeah, there’s Donald Judd and the Chinati Foundation, but Marfa’s real stories aren’t behind museum walls. They’re in the clink of beer bottles at Lost Horse, the early morning heat at Marfa Burrito where Ramona’s hands have wrapped more history into foil than you’ll find in any art gallery.

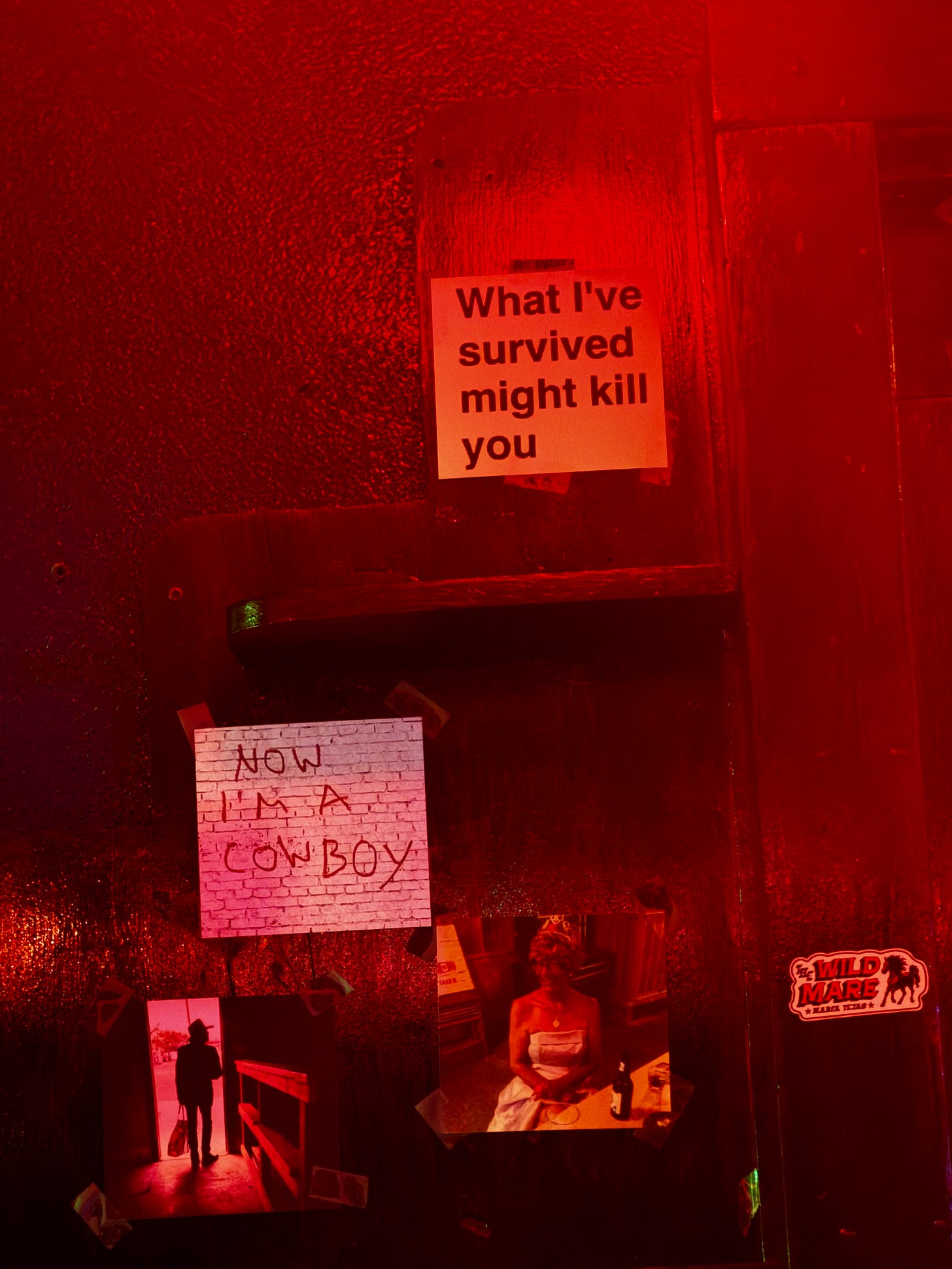

I end my first day in West Texas after closing down Lost Horse and falling asleep under the stars at the Marfa Yacht Club. I met God at the Marfa Yacht Club.

I pull into Marfa Burrito right at opening time the next morning. Ramona’s breakfast burrito—fresh eggs, chorizo spiced just right, Pico that hits your tongue with sharp freshness—is culinary poetry, simple and perfect. It’s also the size of a Pomeranian. I finish most of my burrito as I listen to ranchers and tourists talk border patrol, water rights, and how the stars look different after a monsoon. Out here, everyone’s a philosopher when the sun is rising.

OJR Ranch is just past the iconic Prada Marfa installation in Valentine, about 40 minutes west of Marfa. I couldn’t wait to take my mountain bike out and explore the vast openness. Flying down a descent, adrenaline surging, my bike leaps over a ridge and I fly over the handlebars and land barely four feet from an enormous rattlesnake coiled in the sun. Our eyes lock briefly—time frozen in mutual shock—before it flicks its tongue dismissively and slithers away, leaving my heart pounding in newfound respect for the desert's true inhabitants. No actually I met God off a dirt road near Prada Marfa.

Heading back east toward Marfa I stop in Valentine—a town defined by its sheer stubbornness to survive. At Valentine Bar, I meet locals and passersby whose tales of survival and resilience match the landscape around them—vast, harsh, unforgiving. Over yellow bellies, we toast to solitude and stars.

I see a model posing next to a stuffed bobcat. I meet the leader of the Tigua people; their ranch is bigger than El Paso, he says. Also, they’ve been breaking horses for 500 years. Holy shit.

I meet a local who owns nearly 10,000 acres just miles from where Antonin Scalia died quail hunting. Her dad did the cover art for the Eagles.

The bartender, Jason, handed me another yellow belly and said he once saw a rattlesnake eat a jackrabbit whole. Oh, and the Nelk Boys would be coming by soon. What the hell is a Nelk Boy?? (Turns out they’re You-tubers from L.A. who like to cosplay as cowboys at MAGA rallies; any pub is good pub, I guess).

Just a normal day at Valentine Bar. I leave just before close and start the 30-minute jaunt on Highway 90 to Marfa.

The Davis Mountains north of Marfa call the next morning. Fort Davis is a town nestled amid mountains that seem protective, almost nurturing in comparison. The town and county are named after the former Confederate President—who was born in Kentucky and raised in Mississippi. The air here is crisp, tinged with juniper and pine—the night sky exploding in stars clearer than anywhere on earth. The Davis Mountains provide solace, their quiet trails inviting contemplation. The old fort stands sentinel, a reminder of harsher times, battles fought, and lives lost.

I meet a man named Jim, who used to run moonshine during college and did a stint working for the Cartel. He did it for tuition money and the thrill, he says. His eyes still held fire. We talked about isolation, how locals are being priced out, and about the weird freedom of living at the edge of the map—miles away from the nearest vile of anti-venom.

I hiked up to the McDonald Observatory, still half-drunk, chasing stars that wouldn’t appear for hours. The altitude sobers you up. So does the quiet. From up there, the land rolls out like an ocean made of stone. And for a moment, you get it—why people stay. Why they risk snakes, scorpions, and scorching heat.

West Texas demands honesty. It doesn’t entertain pretension or vanity. It rewards authenticity with unforgettable sunsets, genuine human connections, and starkly beautiful landscapes. Leaving this place feels like parting ways with a truthful friend, one whose bluntness and sincerity you've come to deeply cherish. West Texas, in all its rugged grandeur, stays with you—etched into memory, deeper than words.

Why did I move to West Texas? Because you can hear your own heartbeat out here. You see who you are when no one’s looking.

CPJ | 25 June ‘25 | Marfa, TX